"They hate our freedom"

Those were the exact words used by George W. Bush to describe the motivations behind the attacks on the World Trade Center on September 11th, 2001. The world was divided into "us" and "them," Democracy vs. totalitarianism, peace-lovers and terrorists. The implications were clear: we live in a bipolar world of two civilizations, at war with each other, with no moral, social, or political common ground. Bush's use of this dichotomy may have seemed novel for the American public at the time, who have been beating us over the head with it ever since, but it was only the latest high-profile example of a long-standing tradition in the imperial culture of the West of creating an "other." It is the same dichotomy that Edward Said so famously derides in his seminal work, "Orientalism." The truth is, that there is only one "we," and all people--Arabs included--are part of it, and we all very much have the same motivations. If the wave of uprisings spreading across the Middle East are any indication, Arab democracy is doing better than American democracy. And honestly, they're proof--once again--that democracy is more complicated than stuffing a sheet of paper into a box every-other year.

We can all be victims of this culture of moral superiority. Being born in the West, and being constantly bombarded by this propaganda during my more formative years, it's hard to not to propagate it. Even as I write this, I find it pretty fucking lame that I feel compelled to connect everything going on in the Middle East back to September 11th in order to make it somehow more relevant to a Western audience--as if Arab uprisings aren't important enough on their own.

But the reality is, goings-on in the Middle East are inevitably interconnect with West because of the policies created in the aftermath of that moment, but also the decades of colonialism that preceded it. In the post-9-11 world, a raft of scholarship in the West has been dedicated to finding out about the sentiment on the Arab street. As the US-UK Iraq invasion of 2003 proves, Western intervention is far from being a thing of the past, and didn't end in the era of independence. The constant meddling in the politics of the region has left Arabs feeling dis-empowered, disenfranchised, and, generally, not capable of true self-determination. Even in these very uprisings, the steel, tear gas canisters shot at the protesters in Cairo read, "Made in the USA" on their sides.

How could Arabs feel confident in the West's export of "democracy" if all of the police states constantly breathing down their shoulders were Western-backed?

The West keeps shaking thing up. And like a well-shaken can of soda, the years of pent up frustrations are explosive. Opening the can is what the uprisings are accomplishing, but the rebellions remain largely directionless. Once the angry, immediate reaction is finished, the soda settles and essentially remains the same--except flat and lacking its inertia. Similarly, the revolts in the Middle East run a very real risk of burning themselves out in the long run. What they lack in ideology they make up for in anger, but is this visceral reaction sustainable?

Again, we find ourselves dealing with issues of distrust.

During the Cold War, Communism always proved to be a popular antithesis to US-backed states in the Middle East, because it was a very real alternative. In the Arab world, Communists were continually jailed, their parties outlawed, yet their ideology absorbed by the ruling regimes of the region. The wake of the fall of the Soviet Union, however, created a power vacuum for resistance movements. In a very pragmatic way, Muslim Fundamentalists recognized an opportunity to fill this space, and started filling their ranks with the hungry and disenfranchised in the street. To many, this was a satisfying alternative to both Western capitalism and atheist Communism. Until these rebellions, right-wing Islam, especially the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, has been the only real alternative to the dictatorships like that of Mubarak. Of course, the majority of people still felt out-of-place and out-of-touch with both of these movements, and were left with nothing but to feel angry, yet powerless.

Unlike Tunisia, Egypt's pro-democracy movement has a figurehead in former UN International Atomic Energy Agency Director General, Muhammad ElBaradei. But this is no pining for leadership, instead, it's a lack of cohesive ideology that threatens to pose a problem. In the end, it may be the very reason that the movements may be co-opted.

Perhaps the most classic examples of altering political systems in one's favor, comes to us from Latin America. Where, throughout the 20th century, thanks to the Monroe Doctrine, the US intervened in both full-out invasions and covert operations no less than 22 times to overthrow democratically-elected governments, put down revolutions, and break strikes. The most famous of these cases is the September 11th, 1973 CIA-backed coup d'etat in Chile against democratically-elected, Socialist president, Salvador Allende--and then replacing him with Pinochet. Across all of these cases, a dominant pattern emerges. The United States supports people's movements and democracy--to an extent. When too many anti-American or anti-capitalists get elected, the army steps in to maintain order and protect US interests. Of course, this has taken place in other parts of the world, like the UK-backed overthrow of Mossadegh and subsequent installment of the Shah in Iran. And since the last decade of the 20th century, the US has very overtly, increasingly shifted its interest to the Middle East.

Like parts of Latin America, the Middle East is a popular tourist destination for Westerners. In fact, Tunisia and Sharm el-Shaykh in Egypt are like Europe's versions of Cancun and Acapulco for Americans. Because of this, Western governments will no doubt find instability in these places to be problematic. After all, since they considerable amount of money to prominent politicians, it is likely that rich Europeans will put considerable pressure on their governments to stabilize these areas, so as to not cut in on their party time. US intervention, most likely covert, also poses a threat.

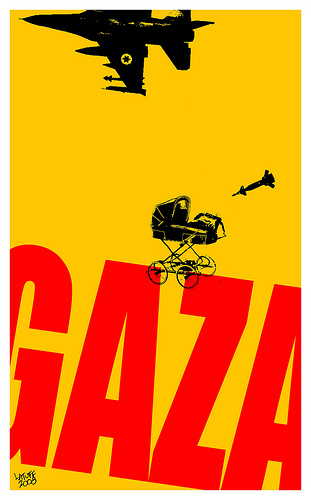

After Obama essentially kowtowed to Mubarak in an address yesterday, the threat is also increasing. Of course, the US also has its own interests at risk. Since the signing of the Camp David Accords in 1978 by Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin, the Republic of Egypt has maintained a friendly relationship with the State of Israel. Even after ascending to power in 1981 after Sadat's assassination, Hosni Mubarak has faced a great deal of opposition on the street due to his continual relationship with Israel. Likewise, because of its close relationship with its special ally in the Middle East, Israel, the United States may see a change in government or a working democracy (you know, the kind where people actually get to say what they want) in Egypt to be a threat to the peace process that it worked so hard to piece together between the two neighboring states. While the government of Egypt may be friendly with Israel, the people of Egypt still feel empathy for the suffering of the Palestinians under Israeli occupation.

While the pan-Arabism of Gamal Abdul Nasser's era may be a thing of the past, the protests in the Middle East show that there is still very much a "collective soul" in the Arab World. At the beginning of this century, democratic movements occurred in various countries in the former Eastern Bloc, like Belarus and Ukraine, but the one thing that didn't happen was a wildfire spread of those protests to other neighboring countries. This time around in the Arab World, the opposite is happening. As the government in Tunisia fell, people feeling similar social pressures of high unemployment, high food costs, and high repression in other Arab countries protested in solidarity and spawned imitators of Mohammad Bouazizi's self-immolation at Sidi Bouzid. As the collective soul cried, everyone just stopped being afraid.

So far, there have been uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt, and we're beginning to see the fomentation of similar things in Yemen and Jordan. It's spread to four countries in just over a month or so. I can very optimistically say that,soon, we may look at a new Middle East. But if the revolutions' effects are to be long-lasting, they need to take precautions to make sure that hard-fought gains are not easily lost. Back in the West, I can only hope that Americans will ever snap out of their trance and stand up for themselves. Perhaps they should listen to our song "Wine of Power" for some sort of small inspiration in recognizing their own power.

One thing is for sure, no one in the Arab world will forget these days of rage. As I watched Al-Jazeera, I saw a cordon of heavily-armed police enveloped and overwhelmed by a sea of protesters. People defended their voice in the street, mostly peacefully, but also with rocks and bottles when they were threatened. The protesters recognized that those who control them are in the minority. Police officers abandoned their posts and joined the crowd. I've never seen anything like it. It was truly an awe-inspiring sight that reminded me that true people-power does exist. ...All it takes is courage.

-Marwan